An etalytics perspective on AI factories and “Grid to Token” operations

After NVIDIA’s CES announcement – and across many conversations with customers and partners at PTC’26 in Honolulu – one point kept repeating: AI data centers are moving toward warm-water, liquid-dominant cooling, but the sites that win won’t be the ones with the flashiest loops. They’ll be the ones that can adapt control strategies fastest when constraints change.

NVIDIA’s "AI factory" framing captures the shift: these facilities are designed to continuously convert power, silicon, and data into intelligence at scale. In that world, the plant is no longer "a building with IT inside." It’s a single co-designed cyber-physical machine where workload, power delivery, and cooling interact – constantly.

Which means the competitive metric changes from “best-case design efficiency” to:

Sustained output per kilowatt – under hard, shifting constraints

(power caps, thermal envelopes, redundancy rules, water strategy, grid dynamics, uptime requirements, expansion speed).

That’s why the real advantage moves from architecture alone to operations:

The thesis

Warm-water DLC raises the stakes, but control flexibility decides who captures the value.

The best operators won’t hand-tune setpoints and sequences. They’ll run a system where they can change objectives and constraints – and the control layer continuously computes the best feasible operating point.

At gigawatt scale, the math turns brutal. Tiny percentage losses compound into massive value leakage. When an AI factory represents tens of billions in capex and a multi-year, high-throughput revenue engine, a 1% gap in tokens-per-watt isn’t "nice to fix" – it’s billions.

That’s why the differentiator shifts from architecture alone to how well you can continuously operate the plant at the edge of its constraints.

1) Warm-water DLC is a forcing function

Warm-water, single-phase direct liquid cooling pushes supply temperatures up (think 30°C toward 40–45°C in next-gen designs). Physically, that can simplify heat rejection in many climates – fewer hours of chiller dependency, more economized operation, and much better heat reuse options.

%20schematic.png)

But operationally, it does something more important:

It tightens the operating margins and increases coupling.

At warmer supply temperatures, transients and stability matter more. Your "safe, efficient" operating point becomes more dynamic because it depends on:

- load volatility (AI ramps and synchronized shifts)

- weather-dependent rejection efficiency

- equipment condition (fouling, drift, partial-load behavior)

- redundancy posture

- power availability / grid constraints

- heat reuse demand (when heat becomes valuable)

So warm-water doesn’t just change the cooling hardware. It changes what "good operations" even means.

2) The plant becomes a single machine – and local controls don’t scale

Traditional cooling controls (local PID loops + fixed sequences + occasional manual tuning) were designed for a world with slower changes and more stable loads.

What’s different in AI data centers (vs typical enterprise/colo sites)?

- Synchronized, fast load ramps: training/inference clusters can ramp up and down in coordinated steps, creating sharper thermal transients than mixed enterprise workloads.

- Liquid-dominant cooling with tighter thermal envelopes: direct-to-chip loops and CDUs introduce additional control layers, and warmer supply strategies reduce “buffer” for overshoot.

- Power becomes an active constraint (not just a utility): power caps, power smoothing, and upstream power-management strategies reshape the heat-load profile the cooling plant sees.

- Higher utilization by design: AI factories aim for sustained, high throughput – less "idle time" for the plant to recover, tune, or stabilize between events.

That combination is why local loops and fixed sequences break down: the optimum operating point moves faster, margins are tighter, and instability during transients becomes a first-order constraint – not an edge case.

When controls aren’t coordinated, you get real mechanical failure modes – not just "inefficiency"

In an AI cooling plant, local controls can create unintended interactions that increase both energy use and operational risk. A concrete example:

- The plant is configured for a high-load / high-flow scenario, so the primary pumps maintain a high differential pressure (Δp) to ensure worst-case availability.

- At the same time, several CDUs are only drawing a small share of capacity (low demand on the secondary side).

- To hold their local targets, the CDUs (or branch controllers) close control valves and reduce flow request.

- The primary pumps keep pushing against a system that is increasingly "closed." Δp rises, the pump moves toward an unfavorable operating point, and the system becomes noisy/unstable (hunting).

- In the worst case, you trigger alarms or protective behavior: pump trips, oscillation, or forced bypass, exactly when you’re trying to maintain thermal stability.

This is the core point: without plant-wide coordination, local "correct" behavior can create system-wide instability – and operators compensate by running more conservatively than necessary (lower supply temps, higher pump head, more trim cooling). The penalty shows up as both wasted energy and reduced usable operating margin, especially during ramps and fast load shifts.

3) What winning operators will standardize: the control framework, not the sequence

AI facilities will inevitably become more heterogeneous: different rack generations, different chip envelopes, different site designs, different heat rejection/reuse paths. But the goal isn’t to build a bespoke control sequence (or a bespoke mechanical workaround) for every exception. The goal is the opposite:

As much variability as needed – with as little complexity and cost as possible.

That’s why the winning sites won’t standardize a single static sequence and copy-paste it everywhere. They’ll standardize the control framework – and let optimization adapt locally inside clearly defined guardrails.

The winning posture: objectives + constraints, computed continuously

Operators don’t want to hand-tune loops to handle every new rack type, grid cap, or heat reuse requirement. They want to set intent:

- "Keep GPU inlet temps inside this envelope."

- "Minimize total plant kW subject to redundancy rules."

- "Avoid adiabatic cooling in dry season."

- "Constrain peak power draw due to temporary grid limits."

- "If asset X is degraded, shift strategy but remain stable."

…and have the control layer continuously compute the best feasible operating point – so the site can handle variability without continuously adding operational complexity.

That’s where flexibility becomes the advantage: not "we can run warm water," but "we can change the rules and still run optimally without manual tuning."

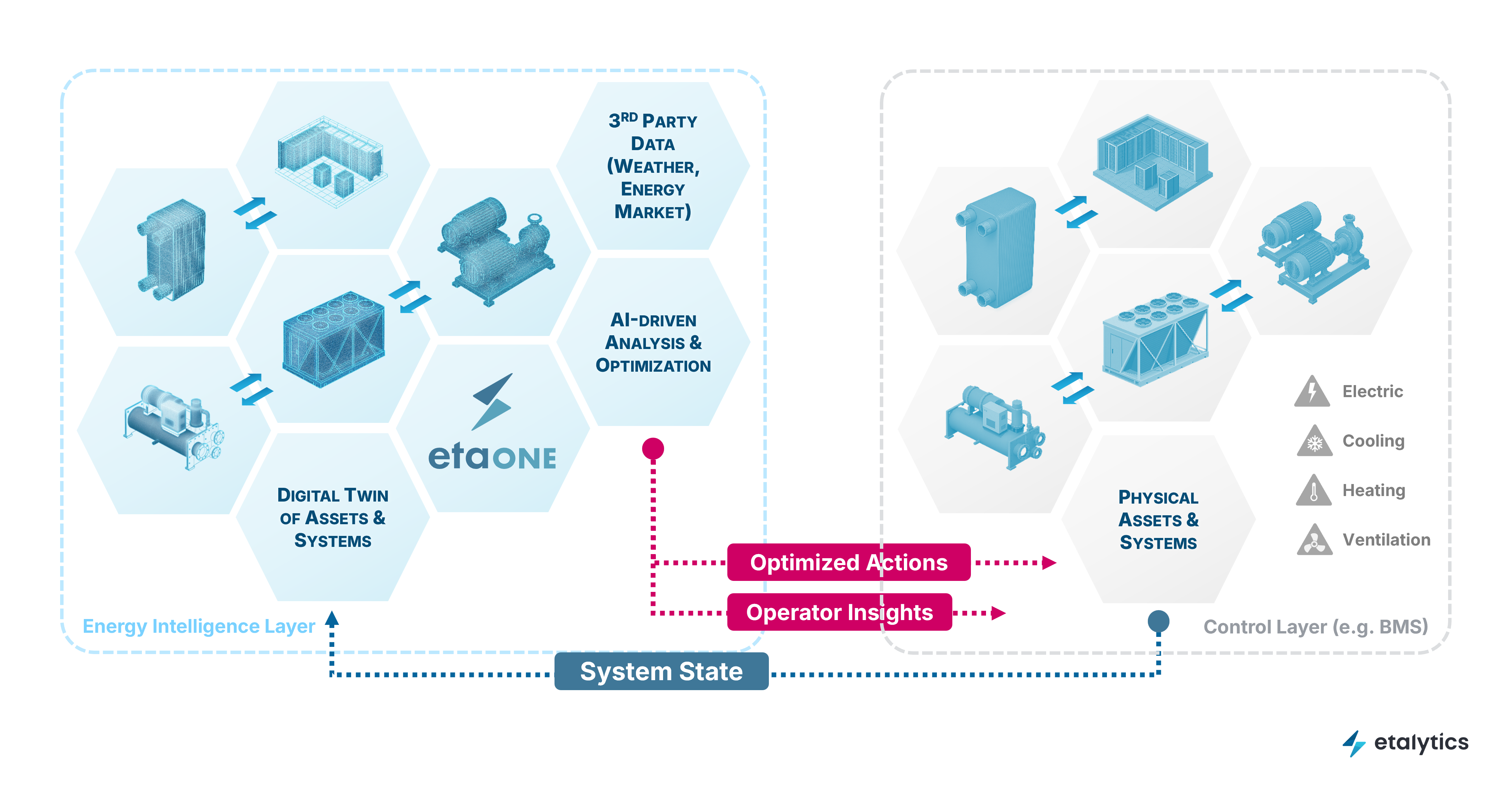

4) Why the digital twin becomes operational infrastructure

Once you treat control as "compute the optimum under constraints," you need a model of how the plant behaves end-to-end – not as a design artifact, but as a runtime tool:

- capturing interactions across loops and equipment

- evaluating tradeoffs (temperature, pumping, trim cooling, reuse, water, power caps)

- supporting rapid “what-if” changes (new rack type, new constraint, equipment downtime)

- enabling safe iteration: validate before you roll changes into production

This is where "digital twin + optimization" becomes non-negotiable – not because it’s trendy, but because it’s the only practical way to run closer to the edge safely as constraints shift daily.

At etalytics, that’s the heart of the perspective: the best sites won’t feel more complex to operate – because control becomes AI and digital twin driven software.

5) A practical operator checklist

Control readiness for warm-water, liquid-dominant AI facilities

- Observability

▢ reliable supply/return temps, flows, DP (per loop)

▢ end-to-end metering of thermal and electrical flows

▢ health signals (approach temp drift, fouling indicators, actuator performance)

- Actuation

▢ variable-speed pumping where it matters

▢ valves that shape flow predictably (not just open/close logic)

▢ heat rejection staging that’s efficient at partial load

- Safety vs optimization separation

▢ deterministic safety layer (hard limits, fallback modes)

▢ optimization layer allowed to operate inside those constraints

- Operational digital twin

▢ fast "what-if" capability

▢ frequent setpoint recalculation

▢ traceability: what changed, why it changed, and what bounds applied

Closing: The smarter loop wins

Warm-water DLC is a technical milestone – but it’s also a strategic forcing function. It makes the real game obvious:

The differentiator is not a colder loop or a new CDU.

It’s control flexibility: the ability to adapt objectives and constraints quickly – and stay stable without human tuning.

The winning sites will be the ones that:

- model the plant end-to-end with an operational digital twin,

- operate via objectives and constraints (not static sequences),

- coordinate thermal and power realities,

- and update setpoints continuously – autonomously, but governably.

That’s what "next-level cooling" becomes in the AI factory era: a smarter loop that stays stable under change.

In practice, operators often see double-digit reductions in cooling energy, and under the right baselines and scopes, outcomes can be significantly higher.

Curious what control flexibility would unlock in your facility?

Reach out to etalytics and we’ll run a quick assessment: your binding constraints (thermal / power / water), your available setpoint degrees of freedom, and what savings + stability improvements are realistic.